LC#23: Parody Movie

On the disintegration (and multiplication) of the parody, from Mel Brooks to YouTube.

Hello folks, a belated happy new year to you. I had a pretty shitty holiday break (got Covid, am pretty much OK now thanks) so I’m opening 2022 with a pretty uplifting topic: the death of the parody movie. I’m not talking death-death, but definitely a sort of decomposition, at least compared to the comedies that raised me. Scroll a bit further down to see what I mean.

Did I mention I’ve been ill? Please allow a lazy link that is very similar to one I shared last year (it is a sequel, but still).

It’s easy to take good parody movies for granted, until you realize they have almost disappeared. I am not talking about generic comedic takes at cinematic tropes (stuff like Zombieland or Shaun of the Dead), but sarcastic rip-offs specifically aimed at well known stories and characters. In other words, the type of Mel Brooks movies I grew up with: Spaceballs (which I have definitely watched more than Star Wars, the object of its satire), but even Robin Hood: Men in Tights or Dracula: Dead and Loving It. Now I know those flicks represent the declining phase of Brooks’ creative parable, but even if they are not on par with the director’s daring meta-narrative experiments (The Producers, Silent Movie) or award-winning classics (Blazing Saddles, Young Frankenstein), his 1980s-1990s takes on American blockbusters were still pretty solid films. Coming from theater and having experienced all aspects of entertainment and movie-making, Mel Brooks was an expert commentator of his medium, and this showed in the way he built characters and gave (often musical) rhythm to both sequences and plots, enriching more mainstream pop cultural references with folksy injections of yiddish and Jewish humor.

I think we can agree a structural, linguistic understanding of the movies one draws from and a sensibility for comedic timing are both essential ingredients to a good parody. A third ingredient is arguably the cultural relevance of the material that is being satirised, which (beyond the internal timing of the movie) gives the overall work a degree of timelessness. Earlier Brooks films were built on relatively classic stuff, but with time the distance between his parodies and their targets seemed to grow a bit shorter: Spaceballs came four years after the third Star Wars movie (and the trilogy had started a decade earlier), while both Robin Hood and Dracula were obviously tailing the success of films produced only a couple of years earlier. There’s nothing wrong with that per se, but I believe Brooks was ahead of a curve we can now fully understand, as the growing demand for parodies and the decreasing distance from their original targets have definitely impacted the evolution of the genre over the years.

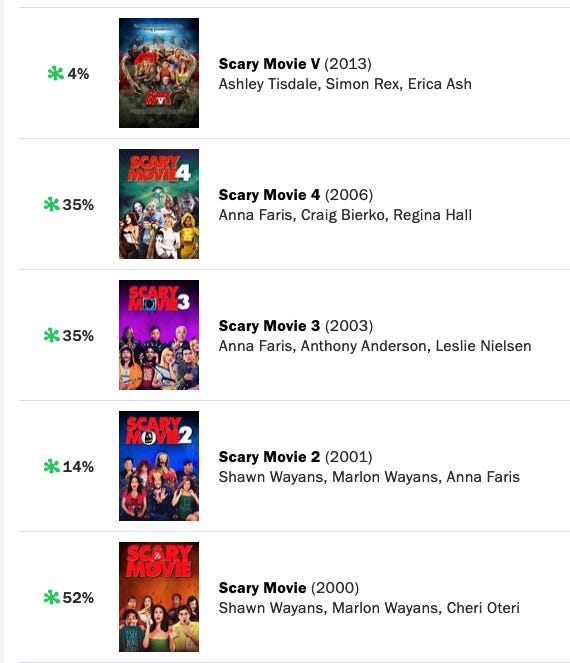

The Scary Movie franchise is a landmark example of this. Picking primarily from Scream, the first movie felt faster than other parodies and drew from a wider range of movies and contemporary pop cultural references than the Mel Brooks films mentioned above. This was not radically different in essence (and we cannot discount obvious differences in terms of style and context), but I remember the movie was a bit of a turning point in terms of how much the gags depended on knowing stuff that was only a couple years older. That only accentuated in the second film, which felt disjointed and much worse than the previous one. Interestingly, from the third movie the direction changed and David Zucker (of Naked Gun fame) replaced the Wayans brothers, who had helmed the first two installments. I always liked Brooks more than Zucker, but his slapstick- and sketch-oriented approach had definitely some affinity with the brand. Nonetheless, while his Scary Movies fare a little better on Rotten Tomatoes, we can see critics did not quite appreciate how the franchise evolved (or the fact that it stuck around that long).

I think the Scary Movie series can be seen as a sort of overlap between the Brooks/Zucker generation and a younger one, influenced by a wider range of cultural contexts and media. Jason Friedberg and Aaron Seltzer, two writers from the first film, eventually became the captains of the now sinking ship formerly known as American parody movie. Starting in the mid-2000s, the duo churned out a string of commercially successful yet artistically terrible parody mash-ups, in which nods to flimsier and flimsier cultural references came to replace the plot almost entirely.

Epic Movie is probably the most representative example of Friedberg and Seltzer’s take on the parody comedy movie. As evident from the trailer, we are now in pure collage, quasi-memetic territory: not only do the movies featured belong to completely different genres, their relevance to the advancement of the story is pretty much null. Importantly, beyond obvious jabs at popular blockbusters from the time we also find nods to a nascent celebrity culture (Paris Hilton) and references to the Internet that had never been as direct (the evil witch in Gnarnia has Saddam Hussein in her MySpace top 8 - yes, this was 2007). If the literary, theatrical or cinematographic references of the early Mel Brooks could aspire to a level of timelessness, this was the beginning of a parody-making that could not discount the present moment as its only ground of life and death, and an increasingly global, multi-media cultural lingua franca as its main currency.

Whether we believe the parody comedy movie is dead or just agonizing, we have to admit bad or opportunistic directors and writers are hardly single-handedly responsible for its decline. The current moviescape is dominated by fandom, reboots, trilogies, universes, and all of that is tightly interconnected and self-referential in ways that are often overtly ironic or even self-parodying. On the other hand, parodic formats have sprawled and proliferated online, to the point that we can consider them the backbone of contemporary digital cultures. Memes, reactions, the pitch meeting video above… everything that comes out is preceded and followed by waves of parody content. On a technical level there is of course the readiness afforded by cheap production tools, but on a cultural one the conversation has become more and more sophisticated. Never has the movie-making process been this transparent and familiar, and since stories are continuously recycled some formats (see clip above) shift the parodic focus onto the industry itself, with its cynical dynamics and predictable strategies. We might not be able to say the same about movies, but it turns out parody is alive and well.